|

1850s Ticket to Ride, Courtesy of Phil Goldstein's Fabulous Train Web Site

|

Was

Foster Avenue, which extends from Flatbush to Canarsie, named for James Foster? He was “among the early settlers in Jamaica, Queens County,” per an unsourced entry

in Brooklyn by Name by Leonard Benardo & Jennifer Weiss (NYU Press,

2006).

|

| 2006: Brooklyn By Name Excerpt |

Kevin Walsh’s fabulous Forgotten New York website found it

difficult to accept this solution and I agree. Based on my research the street

was named for Charles Foster, a founder of Parkville (née Greenfield), which is where Foster

Avenue originates and where it first appeared on a map. Here are the

thrill-packed details.

In 1850 the Coney Island Plank Road Company laid wooden boards – “planks” – along a pre-existing dirt path extending from today’s Prospect Park Southwest all the way to the shore. The wood was replaced by rails in 1862 to allow for horse-drawn “omnibus” (hourly) cars, followed by electric trolleys in the 1890s, until 1956 when the rails were paved over for the B68 Coney Island Avenue gas-guzzling bus.

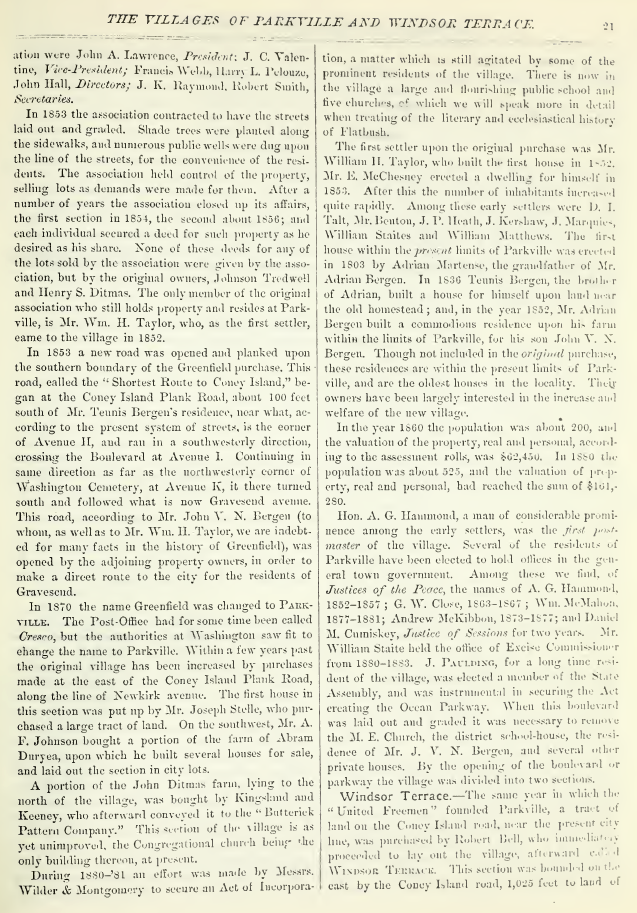

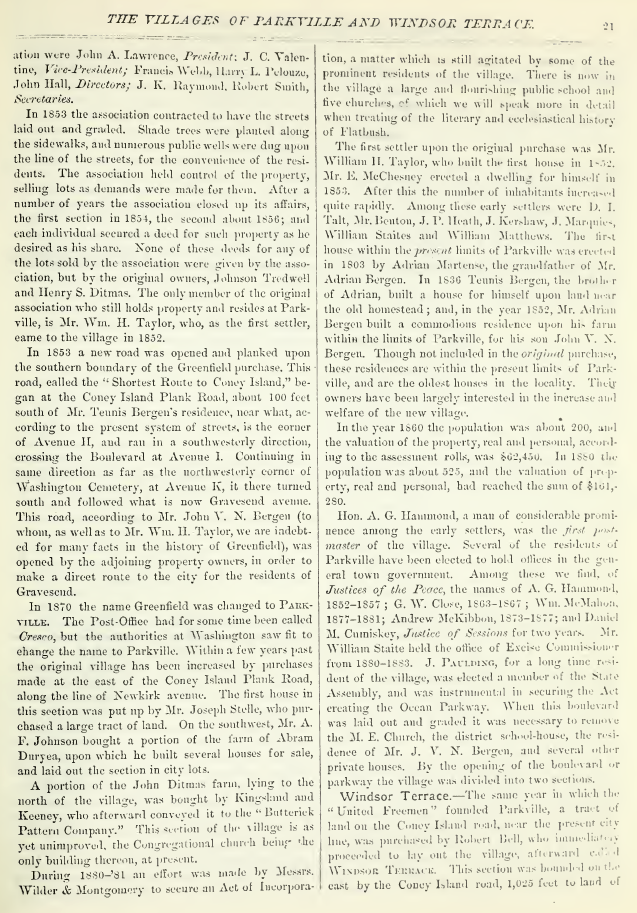

The Plank Road was a dramatic improvement over dirt and mud, making empty land on either side of its right-of-way suddenly more desirable, resulting in the development of two new villages on the Flatbush western border. Windsor Terrace sprang up to the north, and in the far south, from 1851 to 1854, the United Freeman’s Association purchased 114 acres of farmland (including a western slice of the Henry Ditmas farm), laying out a village they called Greenfield.

The principals of this Association, a rural forerunner of real estate development companies, included its President, John A. Lawrence, and another original major land-owner, Charles Foster, who served as a Director.

|

| 1855 Brooklyn Business Directory |

|

| 1854 Oct 7: Foster Ave Debuts |

Not surprisingly then, the first appearance of “Foster Avenue” in the press occurred in the October 7, 1854, edition of the Brooklyn Evening Star, advertising the sale of new houses built on “Foster Avenue” between 1st and 2nd Street in Greenfield. Two weeks later in the same newspaper, a vacant lot was advertised for sale on a street never referenced before – “Lawrence Avenue” – near 2nd Street (today’s Seton Place). Foster

& Lawrence were the only avenues in Greenfield not named for famous

Americans: Ben Franklin (now 18th Ave.), George Washington

(now Parkville Ave.) and Daniel Webster were so honored. Of interest,

Webster died in 1852, just as the Village roads were being created. But James

Foster of Jamaica had been dead for nine years by then and certainly would have

been an odd choice, having no connection to Greenfield.

And just who was Charles Foster? He had a livery business on Gold Street in downtown Brooklyn and worked with John White to bring omnibus transportation from the City of Brooklyn south to Greenfield and beyond. White also owned land in Greenfield and to the east of the Plank Road. In fact, White Street was the original name for a path that ran from the Plank Road to Ocean Avenue which is now called Newkirk Avenue (after a Dutch farm owner located further east at today’s Brooklyn Avenue).

|

| 1852 Oct 19 Brooklyn Eagle: White & Foster to Run Horse Cars in South Brooklyn |

.jpg) |

| 1870 Map of Parkville was super-imposed on the street grid promulgated in 1873 by the Town Survey Commission of Kings County (formed 1869). This map created by the Post Office led to adoption of the name Parkville for the area that Greenfield villagers adopted. "NY & Hempstead RR" below Parkville was a proposed steam rail line that would be built in 1877 as the Manhattan Beach RR spur of the LIRR, now part of the Interborough Express proposal. |

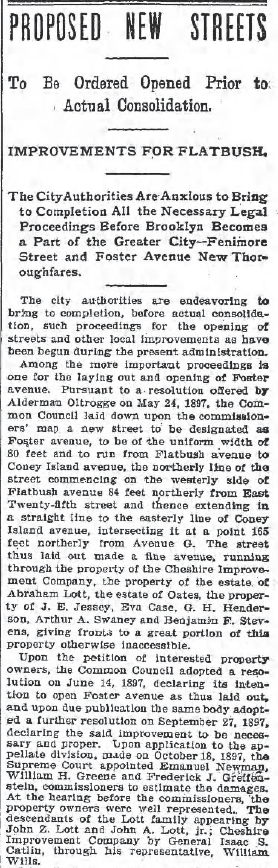

There are other reasons to reject Jamaica’s James Foster. Significantly, Foster Avenue did not extend east of Parkville until 40 years had passed. As documented in 1897 hearings before the Brooklyn Common Council, an unnamed narrow path that cut through some farmland from Coney Island to Flatbush Avenues would be widened and named Foster Avenue as well.

|

| 1897 Nov 28 Brooklyn Eagle Pt 1 |

|

| 1897 Nov 28 Brooklyn Eagle Pt 2 |

.jpg) |

| 1897 Summer: Vanderveer Park Ad-Avenue E Still in Use |

Five

years later, Foster was extended again, when the Germania Real Estate &

Development Company, having founded Vanderveer Park, successfully petitioned

the City of New York to extend the name of Foster Avenue eastward from Flatbush

to New York Avenue in order to replace the boring street grid name of “Avenue E.”

Of note, the only use of the land east of Flatbush Avenue prior to the 1902 Vanderveer

development was the Flatbush Water Works which built wells at the head of the

Paerdegat Creek in 1881, using an address of "Avenue E at New York Avenue."

|

| 1902 Feb 18 Brooklyn Citizen |

|

1890 Insurance Map: Kevin Walsh annotated where Avenue E would become an extension of Foster in 1892.

Note "Paerdegat Lane - a narrow dirt road that wandrered west to Flatbush Ave - disappeared in the 1920s (see an earlier post for more). |

.jpg) |

| 1890 Paerdegat Pond Near Flatbush Water Works |

|

| 1890 Flatbush Water Works on Avenue E |

Beyond

New York Avenue, south of Foster Avenue there were no streets, just woodland,

until 1940 when Fred C. Trump (the former President's father) cut down the Paerdegat

Woods – the last existing natural woodland in Brooklyn – to erect hundreds of

brick houses. After another extension, Foster Avenue ended near the grade

crossing of the L train at the East 105th Street station in Canarsie

– the last grade crossing in Brooklyn, eliminated in 1973. Many maps tell this tale

of Foster Avenue’s progression.

|

1929 Paerdegat Woods at E 37th St Looking North to Foster

|

|

| 1940 May 19: NY Times |

As for Jamaica’s James Foster, Census records indicate he owned two slaves on his Queens farm from 1790 until New York abolished slavery in 1827. He also was a mover-and-shaker who became a principal of the Brooklyn Bank on Fulton Street. And in 1836 he was accepting bids for the repair of the Brooklyn, Jamaica and Flatbush Turnpikes. The toll booth for these dirt roads was originally located near the Long Island Rail Road’s terminal at the intersection of Atlantic & Flatbush Avenues. This last fact might account for his being erroneously associated with Flatbush’s Foster Avenue.

|

| 1881: Excerpt from The Social History of Flatbush by Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt |

|

1850s Ticket for Horseman Using the Plank Road, Courtesy of Phil Goldstein's Fabulous

Train Web Site |

|

| 1881: Excerpt from The Social History of Flatbush by Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)